In this week’s Good Faith podcast, David French and Curtis Chang tackle the tough question every Republican of good faith should be asking: Should I stay or should I go? This question is highly relevant for everyone, regardless of political affiliation.

Editor’s Note: The following excerpt is heavily edited for clarity and brevity. To hear the full discussion on The Good Faith podcast, click here or watch the above video.

CURTIS CHANG: Joining me today is founding friend, David French. David is the co-founder of the original Good Faith podcast and a columnist at the New York Times. I cannot think of anybody else I would rather have this discussion with, on this topic: “Should I Stay or Should I Go, the GOP Version.”

I thought of this topic at a recent gathering, “A Conservative Agenda to Protect Democracy.” The participants were mostly classic conservatives, pro-liberal democracy, and Christian. The crowd was full of think tank leaders, foundation executives, a state Governor, a Lieutenant Governor, a Republican Secretary of State (at the state-level), and many election officials who’ve been on the front lines of some of the most contested, controversial local elections. Almost all of them were Republicans, except me, and they all complained about how much the GOP has been “taken over by the crazies.” They all noted the dysfunction of the party.

I fit the profile in some ways but not others. I identify as a Burkean progressive, which means I believe in many conservative principles but also believe in some of the progressive agenda. I haven’t been an actual member of the Republican Party for quite some time. The value of an outsider, when coming into a troubled institution, is to ask the dumb question. That’s what I did. On the last day of the conference, I asked, “Guys, why don’t you just go? I mean, if the party has been taken over by the crazies, if it’s as dysfunctional as you said, why do you stay?”

There was a lot of silence in the room. People were musing.

“Well, that’s a good question,” some said. “Maybe we need to think about that question more seriously.” Some provided a decent answer to that question, and others were a little defensive. There was a lot of angst and confusion.

My question touched a nerve. That’s when I called you and said, “David, we need to talk about this.”

David, why does this question actually matter for everyone? Not just for the Republicans who are still wrestling with staying in the party, but really for anyone who’s already left. Also, frankly, for Democrats or people not aligned politically: why should they care about how Republicans wrestle with this question “Should I stay or should I go?”

DAVID FRENCH: Watching a large group of people wrestle through a challenge to their traditionally expressed morality – when that traditionally expressed morality carries with it a real cost – has many lessons. You’ll learn positive things, you’ll learn negative things, and then you’ll also, hopefully, absorb lessons that will prick in your mind, your heart, and your conscience. Not if, but when you face conflicts between different aspects of your identity. We all have different parts of our identity: husband, father, Republican, boss, employee, Christian (not necessarily in all that order). But sometimes our identities come into conflict with each other. Only then do we learn where our true hierarchy of values lies. Not in the abstract, but in the concrete.

CURTIS CHANG: Does how Republicans answer this question have real political effects for the rest of us?

DAVID FRENCH: Partisanship can lead you to cheer the dysfunction of the opposing party.

You believe the dysfunction of the opposing party might make it more likely for “your side” to win in a divided nation with two parties. But it’s bad if an unhealthy party is the only other option when voters want to send your party a message. Even if you think that your party is not as dysfunctional as the other party and that your party has higher integrity than the other party, your party is not infallible. It’s going to oversee some negative events and might be responsible for some negative developments. The only way to hold “your side” accountable is by voting for the other party. That’s why we need two healthy parties. And the definition of healthy is not “agrees with you.” The definition of healthy is “are they thoughtful, are they seeking the common good, do they have integrity? Do they tolerate potential disagreement and dissent? Do they subscribe to our social compact around the Constitution?” These are key questions.

CURTIS CHANG: Let’s speak explicitly. Democrats should not cheer the dysfunction and authoritarian impulses in the Republican Party, just because the Democrat side is more likely to win an election. You may lose an election, because your party may screw it up somehow, and then you’re going to face an incredibly tense election, where stakes are so high. Because if you lose, you are handing things over to “the crazies.”

DAVID FRENCH: We shouldn’t even have to explain this to be honest. But in 2016, many Democrats were quite happy that Donald Trump won the nomination. Some Democrats are already rubbing their hands together in glee at the thought of taking on Trump in 2024. I agree that Trump is easier to beat than any number of other Republican politicians. But what are the consequences of a loss to Donald Trump?

Democrats have been playing with fire. There was a lot of funding that flowed to some very far-right candidates in 2022 who defeated the anti-Trump candidates.

CURTIS CHANG: Representatives who voted for the impeachment of Trump were defeated in the primary, because the Democratic activists funded Trumpian opponents.

DAVID FRENCH: They actually dodged the bullet, because all of the hyper far-right MAGA Trump-enthusiasts that they poured money into actually lost in the general election. Many people say, “Look, it worked.” No, you just played with fire and didn’t get burned. That’s all that happened there.

A year or two ago, Democrats laughed at Marjorie Taylor Greene. “Look, the Republicans put somebody in Congress, who believes in Jewish space lasers.”

Now, nobody’s really laughing, because she’s a very powerful member of Congress – not because of her formal position, but because of her grassroots reputation. She was elevated because so many people on the left laughed at her. That’s how dysfunctional things are. All it takes in some Republican circles – again, not everywhere, but some Republican circles – for someone to become really popular is if they’re mocked or derided by the other side. Not whether they have natural political gifts, character, or integrity. People need to be aware of the dynamic. The more the left comes down on somebody on the right, the more the right rallies to that person.

Editor’s Note: Curtis positions this issue using a metaphor:

CURTIS CHANG: Imagine you are a member of a ship traveling across the ocean and are attacked by pirates. The ship is your institution (whether it’s the GOP, the Evangelical Church, or another institution) and you are being attacked by pirates wanting to take over your institution with a corrupt, evil version of the original institution. They want to fly the pirate flag and take over your institution. So what are your options when you are being overtaken by pirates? Your three options are LEAVE, STAND, or HIDE.

Editor’s Note: Below are the conversational highlights of each of the three strategies.

LEAVE

CURTIS CHANG: Here’s a scenario. It looks like the pirates are going to win. They’ve taken over the rigging, they’ve taken over the foredeck. You feel like they’re about to win, or you just can’t stand fighting anymore. You’re just not a fighter.

In that situation, it is a legitimate option to leave, but how you leave matters greatly. If you jump ship alone, your chances of surviving are slim, because we can only make it through the ocean of life with partnership with others to make it through a long, hard journey.

We can only make it through the hard things in life when we’re together, and institutions bring us together. To try to survive alone is like jumping into the ocean alone. Maybe you can grab a broken spar here, a casket here, and you can tread water for a little bit. But you won’t make it for very long. You need others for support, encouragement, shared resources.

Alone, you are disoriented. You need others to make sense of this new world, to figure out a new course. Your best chance of success is to find a lifeboat – a little other institution or organization, where you can gather with others and fly your own flag. This will allow other individuals (who have jumped ship, are treading water, and flailing about alone in this ocean) to find a spot on the horizon to swim towards and cling to. Together you can shake off the damage and try to chart a new, unknown course.

David, after you left The Good Faith podcast for the New York Times, I kept this podcast going, because we are a lifeboat. We aren’t anybody’s final destination, we’re not a long-term institution, we’re a lifeboat.

DAVID FRENCH: The way you described leaving is actually a form of fighting. A fighting withdrawal. It’s the way in which many times causes are preserved.

The last thing you want to do is “quiet quit” or “ghost” the GOP. A lot of us don’t have other lifeboats close. You can find them on the internet, listen to this podcast, subscribe to The Dispatch, read me at The New York Times. Sometimes it’s hard to find other “lifeboats” in your local community.

But, there is a real value in not “quiet quitting.” We are in a world, in which the most extreme voices feel completely uninhibited in speaking. You might feel intimidated to state what you’re doing and why, even in a small community, even in a situation, where you don’t necessarily have a public platform beyond your own social media. But what you’re doing is a form of fighting, especially in a political structure, where quitting is its own form of voting in a way. Walking away from a party is your own form of citizen activism by saying what you’re doing and why you are doing it. You are providing a degree of accountability, because the pirates are not quiet at all.

CURTIS CHANG: There’s nothing quiet about the Jolly Roger. Pirates tend to be loud. There are a million human and super understandable reasons to quietly go away. But when you openly declare why you’re leaving, you are refusing to consent to being a part of an organization going astray.

David, why have we seen so few examples of this lifeboat option, of fighting withdrawal in a collective, organized fashion?

DAVID FRENCH: There’s a lot of fear, if you’re doing anything other than quiet quitting, there are consequences, okay?

CURTIS CHANG: The pirates see that flag, and they’re going to actually aim a cannon after you.

DAVID FRENCH: Exactly. It’s so much easier, just on a relational basis (especially if you live in a really red area) to keep your mouth shut. An enormous number of people, especially in the hyper-mobilized Right, who intentionally inflict real costs. Maybe you’re going to vote for an independent or a Democrat, instead of a Republican. You’re going to do it quietly, because of disincentives towards speaking up.

The other thing is ignorance, and I don’t mean that in a negative sense. People just don’t know there are other people who feel the same way, because there aren’t actually a lot of institutions on the Right waving a flag. Time and time again, I run into people who tell me, “I haven’t really felt like a Republican since 2016, and I felt alone until I found you last month.” Like wait a minute, you know? I’ve been out there waving my flag.”

But I’m just one small voice in a really big country.

This grieves me the most, because we would have bigger lifeboats and larger communities, where people don’t feel so alone and isolated. I understand the fear but don’t think it’s justifiable. The other part, the ignorance part, demonstrates the sad reality of how small our lifeboats are.

CURTIS CHANG: A pastoral word here. If you’re leaving the GOP, find other like-minded people. You might feel like you can’t be the one to raise the flag or cobble together a little mini lifeboat. But find others – even if it’s two or three people, even if you keep a low profile. Scan the horizon, try to find other folks and swim to them. If you are thinking about leaving, leave with others.

STAND

CURTIS CHANG: So the “stand” option is when you say, “You know, this is my boat, and I’m the true member and flag bearer of this institution. I’m going to make a stand. I’m going to fight it out. I’m going to defend the ship while this institution is under threat.”

Just to be clear: as a Christian, this is a spiritual stand, not a physical fight. As Paul says, our enemies are not ultimately of flesh and blood. We are standing, as Ephesians 6:12 says, against the powers of darkness. Ephesians indicates this stand against the dark powers usually takes place in institutional context – against the rulers, the authorities, the dominions. This is Biblical language for concrete institutions.

How you make a stand is critical. If you try to make a stand alone, your chances of success are very low. You’ll be like one individual on the foredeck surrounded by a mob of pirates, and somebody is going to stab you in the back. Somebody will club you over the head from an unexpected direction, and you will not have anybody else to rely on.

If you’re going to make a stand, you’ve got to find others. And you’ve got to stand back to back, where you can see all the threats coming at you. Together make a stand against the powers of darkness.

This was the rationale for The After Party. If the Good Faith is the lifeboat option, the After Party is the stand-together, rally-us, form-a-circle-on-the-foredeck option. Right now, pastors who want to stand are left to fight the mob alone. The After Party is trying to plant the flag somewhere on the foredeck and say, “Rally to this point, let’s make a stand here.”

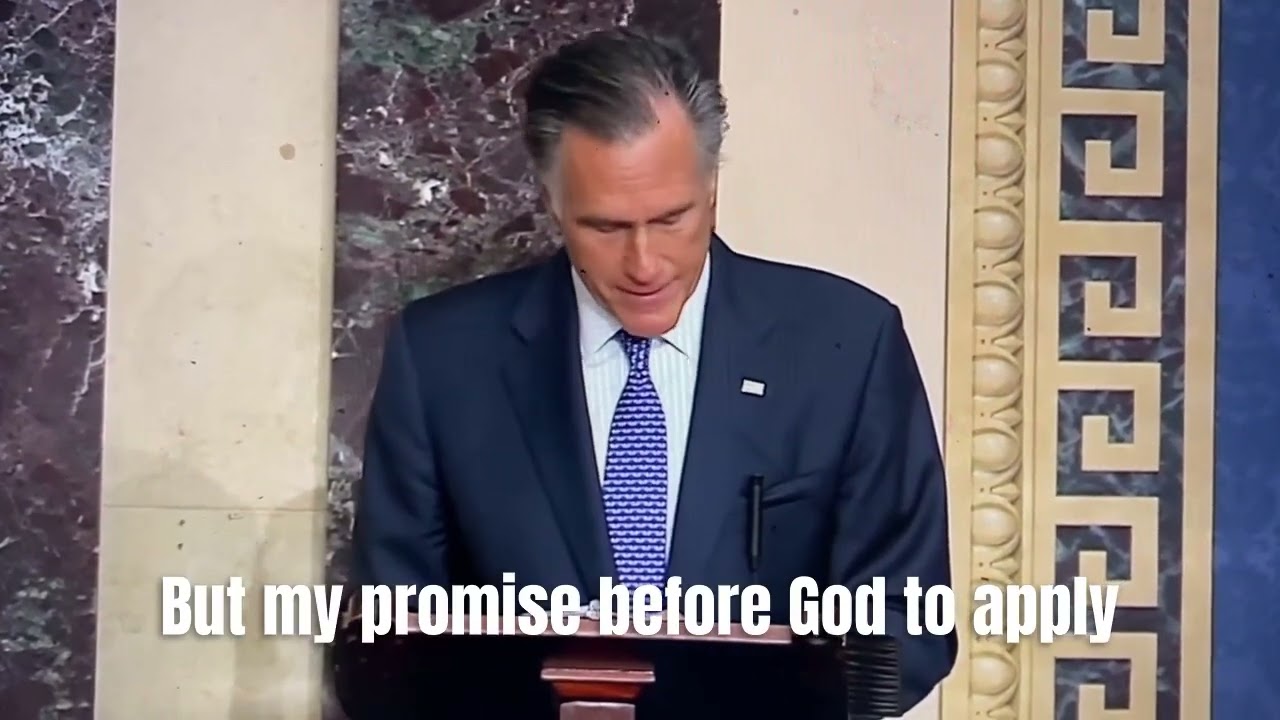

DAVID FRENCH: As you were talking, I was thinking about Mitt Romney (who stood by himself to vote to convict Trump in the first impeachment), Liz Cheney, Adam Kinzinger.

By the end of the Trump era, you actually had a very small number of Republicans in the House who voted for impeachment, and a very small number of Republicans in the Senate who voted for impeachment. There are reasons why it’s such a small circle. The early people, who came out against Trump were massacred and demolished. Jeff Flake and Bob Corker, for example.

CURTIS CHANG: Did they really make a stand together within any organization or were they the individual fighter?

DAVID FRENCH: There was no one for them to stand with. I don’t blame Jeff Flake, Bob Corker, or Mitt Romney for being alone.

CURTIS CHANG: Well, I don’t blame them, but why didn’t they convene, organize and say, “Let’s do this together.” Imagine when the Access Hollywood tape came out in 2016, if Paul Ryan gathered with everyone else who were aghast at this. Imagine if they actually planted a flag and declared together, out loud, “We’re not going to do this.” Why did that not happen?

DAVID FRENCH: That’s an easy answer, Curtis. There weren’t very many fighters, and there were a lot of hiders. Mitt Romney could have worked the phones for nine days straight and talked to everyone who privately told him they didn’t like Trump and believed he was unfit. But he wouldn’t have gotten one more vote to convict Trump.

It’s not like people didn’t try. It’s not like people didn’t say, “Are you with me, are we going to be in this?” At the end of the day, a lot of people behind closed doors said, “I don’t like Trump. He’s a threat to the Republic.” When it came down to the ask – “Are you going to stand?” – the answer was “absolutely not.” They hid.

I don’t blame the fighters. I blame the hiders, who misled the fighters into thinking they might fight. The hiders deceived the fighters into thinking that there was going to be more support. Then, when the fighters stood up, it all evaporated.

I would urge folks to go back, and look at Mitt Romney’s speech that he delivered when he was the first senator in American history to vote to convict a President of his own party. Look closely. His hands were shaking. That’s what it’s like to fight.

CURTIS CHANG: The hiding option is so damaging, because not only does it leave the fighters out to dry, but it completely erodes trust for any collective action, for virtue in the future. You cannot act together, if trust is not there.

This is a great example of why the political future for our country has a spiritual component to it. It is not for the absence of strategy. There are plenty of smart people around. The spiritual components of courage and virtue are missing. No substitute for that. You can’t strategize your way around that. You can’t maneuver or finesse your way around that. (I mean spiritual in a broad sense of that word, the spiritual quality of courage, which is really just virtue under test.)

HIDE

DAVID FRENCH: You can’t understand this moment until you really truly understand the hiders. This is, by far, the biggest segment.

People ask me, “Why did so many Evangelicals vote for Trump?” And the quickest, shortest answer to that is, “because they’re Republicans, and Trump was the Republican nominee.” End of explanation.

The hiders are the most interesting population. It’s easier for me to understand the fighters and the leavers. Why did Mitt stay in the GOP, and fight, and try to cleanse the GOP of a corrupt President? Versus what I did? [Editor’s note: David left the GOP.] I’m not a Senator. I’m an opinion columnist. Those are different positions, with different kinds of cultural roles.

I can understand both of those decisions much easier than I can understand the hider.

CURTIS CHANG: The hider, to be clear, is not a MAGA person. The hider is against the pirates. Deep down, they want the pirates gone, but their rationale is “If I make myself a target, if I leave by planting a flag on a lifeboat, I’m going to be a target, they’re going to shoot a cannon at me. If I make a stand on the foredeck, I’m definitely going to get massacred by the mob. I’m going to hide.”

Let’s just name this justification for what it is: fear and self-protectiveness.

They are telling themselves, “I can out-wait them. If I hide long enough, they will leave, and I will get my ship back.” David, how realistic is that?

DAVID FRENCH: It’s unrealistic. And, hiding makes it more unrealistic.

Hiding is justified by what I would call the prudential justification: “I see what’s happened to the leavers, they’re out there on these very small institutions, they have not built a competing, a truly competing institution to the GOP. I see what happens to the fighters, because I step over their mutilated remains on the deck. Since the pirates cannot sustain themselves and will burn themselves out, therefore somebody’s got to remain. And the only way to be still here in any sort of viable way is this hiding strategy.”

I call this the prudential silence analysis, which actually can seem kind of compelling: “This movement only has a limited shelf life, it’s going to burn itself out. In the meantime, I won’t burn bridges and will be there to pick up the root pieces. No one’s going to call Liz Cheney back to the party. No one’s going to demand to nominate Mitt again for President. But me? I haven’t hurt anyone’s feelings. I’ve been the loyal soldier, and I’ll be the one to pick up the pieces.”

Let me highlight two errors in this thinking.

One: it presumes you’re able to maintain your own virtue while you stay on the boat. Time has not been kind to that thesis, shall we say? There’s an awful lot of people who assured me that they were stayers, but would never buy into MAGA. They were the third bass boat in the boat parade by 2020.

CURTIS CHANG: Just pause on that, because that’s really important to underline: when you hide, you are being formed spiritually. We form ourselves spiritually by the actions we take. And when we hide, there’s a spiritual formation going on. Your spirit of courage is getting drained. To hide you have to practice hiding. “Oh, I see a threat, I’m going to duck my head.” The more you adopt that habit, it forms you over time Another way to put it is, “yes, maybe at some point the pirates will get bored, burn out, and leave. But when they leave, they will have already taken something.” They will have taken it from you, the hider, and that thing that they’ve taken is your courage.

DAVID FRENCH: Timidity is habit-forming.

CURTIS CHANG: Even in this dream scenario, when you inherit the ship after the pirates leave, you’re in no position to fight the next pirate that comes sweeping over the horizon. Why? Because your own courage has been drained from you by a long, formational experience of hiding.

DAVID FRENCH: The other form of the “prudential hiding” argument is: “As bad as these pirates are, they’re not as bad as those other pirates over there. And so I’m going to join with the thieving and plundering pirates to stop the cannibal pirates.”

That’s “team lesser evil” approach.

The problem with the “team lesser evil” argument? It doesn’t work without corrupting you. I’ve never met somebody who can sustain feeling as if they’re evil to any degree. You don’t run around saying about yourself, “I’m part of ‘team lesser evil.’” That’s a bad chant. “Lesser evil, lesser evil.” We don’t want to be evil.

There are two ways we deal with that.

The best way is repentance. If I have embraced or rationalized evil – even if it’s a lesser evil – I should repent, embrace virtue, and hold on to what’s good.

The other way is to say, “You know what? Actually this isn’t lesser evil, it’s actually quite good.” We saw people transition from, “I’m going to hold my nose to vote for Trump” to being the third boat in the Trump boat parade. People rationalized, saying, “Oh, actually this is okay. No wait, actually it’s good.”

Isaiah 5:20 had a lot to say about that. “Woe those who call evil good, and good evil, who put darkness for light, and light for darkness, who put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter.”

This is what really grieves me about what happened on the Right: they began to call evil good and good evil. We just saw this big example of this when Tucker Carlson was fired. A large number of Christian voices came out in support of him in emphatic ways, without any mention of his lying, malice, none of that. They saw Tucker as a very effective warrior against what they perceived as this greater evil. Over time, they began to admire Tucker Carlson fully. His expression, character, and the way that he treated others was often vile. And yet Christians wrapped both arms around him. This is what happens when the two prudential strategies – “I’ll wait it out” or “It’s a lesser evil” – are employed. You end up empowering the very pirates who seized the ship.

CURTIS CHANG: All of what you said is Biblically, logically, and historically true. If you look at every truly evil regime that has risen to power, they have risen to power through that particular logic. People who disagreed thought, “Ah, Hitler. I don’t know if I can go along with him, but he’s better than the other guy.” Or, “I will wait it out and pick up the pieces after he’s gone.”

When Hitler, Pol Pot, or any authoritarian totalitarian rises to power, hiders adopt that logic. Invariably those very people become corrupted themselves. They don’t just wait it out, they become supporters. They become re-formed and re-shaped by the very evil they were trying to hide from and wait out. I’ve been doing a lot of reading about the Weimar Republic and the Christian German Church. That is the logic you see over and over again. They generally found Hitler distasteful for spiritual and class reasons. They viewed him as a young, rash, from-the-streets brawler. But they were like, “You know what? We can use him.” Or “This can’t last forever.” And eventually by the end, they were complete supporters of the Nazi regime. They had become Nazis themselves.

DAVID FRENCH: Let’s just remember the friendliness towards early versions of fascism in the West. Until Hitler made all of his aggression completely, painfully, genocidally known, there was a surprising amount of sympathy for fascism in a lot of quarters in the West. And some of it, to be sure, was rooted in anti-Semitism and anti-communism.

In part of the West, you were seeing Soviet communism, and it was a monstrosity. It was an anti-life, anti-human, genocidal ideology, that had the blood of tens of millions on its hands. So if there was ever a great evil, that fundamentally atheistic genocidal communism was. To be very clear, I’m not saying that atheism and genocide flow from one to the other. If you were a Christian in the West, how were you going to fight this genocidal, communist. expansionist empire? Well, here comes “team lesser evil.” You had the red shirts, and then you had the brown shirts. But over time, “team lesser evil” was not all that lesser evil, was it? It was ultimate evil.

You can be drawn into these highly tactical, highly pragmatic decisions, by the existence of what you perceive to be overriding evil. You can be drawn into what you believe to be tactical, or temporary kinds of alliances, where you sacrifice a lot of things that you would never imagine sacrificing in face of this looming threat. Then you fast forward the clock a few weeks, months, years, and you don’t recognize yourself anymore.

CURTIS CHANG: I want to state this. It has become kind of a standard protocol, that whenever you use the Nazi example, to say, “Now I’m not saying _____ are the same thing as Nazis.”

So I suppose we can insert that standard caveat. But actually the same psychological and spiritual dynamics are in play. The actual evil on the street certainly is not as bad as the Nazis, but the same psychological and spiritual moves, rationale, and justification that led to the Nazi Party are right now in play, both in the Evangelical Church and in the GOP. That’s the danger.

DAVID FRENCH: We can go to other historical analogies. I’ve used the Sunni-Shia Civil War in Iraq as an example of how a community animated by grievance can become quite aggressive. And sometimes those grievances are real, and then sometimes those grievances are manufactured or conspiratorial. Let me put it this way, Curtis. I am less inclined to sort of say, “I’m not saying this or that, after January 6th.”

In December, I was writing articles warning of violence. I saw it coming. You had to have your head in the sand not to see violence coming with all of this rhetoric. But even seeing violence coming, I did not see the storming of the United States Capitol.

I’m at the point where I’m highly hopeful a lot of these darker historical analogies won’t ultimately play out, but I’m no longer remotely certain. If you are certain, you’re probably right. But there’s a big difference between being probably right and certainly right, and we need to drill down on some of these historical analogies.

CURTIS CHANG: David, let’s get a little more pastoral and practical. I think we’ve done a lot of great analysis, but I want to talk to the hiders, those who either self-identify and have some uncomfortable stab of recognition during this podcast. David, what would you say to those people, as they’re coming to some dim starting recognition? What’s their first step?

DAVID FRENCH: Repentance. And to say repentance is not to say I’m standing here condemning you, or that I don’t understand your choice. I understand and sympathize with it. I know what it is like to make a different choice, and it can be really hard and tough. But when we make an understandable wrong decision, the way to achieve lasting change is by repenting of the wrong decision. The first step is to repent, and then the second step is to confess. “Here’s what I believed. I no longer believe it, and here’s why.” Or “Here’s what I did, I no longer believe that was right, and here’s why.”

It’s very good for your soul, and it’s deeply encouraging.

In Tennessee, there was a recent news event in which two Black legislators were ejected from the state House. If that pushed you over the edge, you might say, “I’ve been meaning to say something like this for some time, but I’m done.” Or “I’m done. I refuse to consent to this as a Republican. I have in the past, that was wrong, but now I refuse. From this point forward, I am not going to vote for people who unrepentantly voted to overturn the election, or who voted to expel these members of the House. I’m just not going to do it. I’m not part of this party.”

There are abundant opportunities to tell friends, families, or whoever follows you on social media. That is a very important moment with real practical application.

How many times do you hear, “I thought I was alone. I thought I was going crazy. I thought I was the only person.” When you finally plant the flag and stand on the foredeck, you’ll get incoming. But you’re also going to be a part of a community that you didn’t know could exist.

CURTIS CHANG: I didn’t intend this to be a promo for The After Party, but sign up to get updates about an effort that David, Russell Moore and I are doing. It’s a “rally around the flag” project. Come find out more about it, find out ways that you can be involved as this project unfolds. That’s one way you can make a stand is subscribe and share that with others. You can also share the Good Faith podcast. Tell others about this lifeboat, as a way for you to gather with others to make sense of this new world in which you are no longer hiding. Promote this podcast, put it on your social media, share with others. I’m just offering what we have. There may be others that are expressions of the leave or stand option. Go public with it.

If you feel convicted by anything you’ve heard, find someone who you know will be compassionate, understanding, and is rooted in the gospel of forgiveness. Make a confession, make a confession, and receive forgiveness from God. We are all in constant need of repentance, confession, and forgiveness. That’s the life cycle of a Christian in all areas of life – including politics.

The Good Faith podcast comes out every Saturday. Listen and subscribe here or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Curtis Chang is the founder of Redeeming Babel.

Subscribers to Redeeming Babel will receive a discount on all Redeeming Babel courses, a monthly newsletter, and exclusive access to member only forums.